Remember Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson? Could they help us today?

From 1966 to the early 1980s, two renowned economists, Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson, wrote alternating columns in Newsweek magazine, representing opposing views on economics. This was a time when economics, often referred to as the “dismal science,” gained significant interest from politicians and the public due to the economic problems faced by the U.S. and other countries.

During the 1970s, the global economy experienced stagflation, a period of stagnant economic growth and high inflation rates. This posed a significant challenge for policymakers and economists. No existing economic theory provided an effective solution. Many policymakers looked to Friedman and Samuelson for answers or, at the very least, clues on how to proceed.

Today, the U.S. faces different circumstances, including a $36 trillion national debt growing at a rate of $2 trillion a year. Besides the growing debt, the country has a significant trade deficit, largely due to outsourcing manufacturing and other activities to countries with lower labor costs.

Like stagflation, no existing economic theory offers a pat solution to the national debt. One political party advocates for increasing taxes, while the other argues for reducing government expenditures; for the past 25 years, no significant action has been taken. Moreover, without drastic, politically undesirable changes, neither of these paths would lead to a balanced federal budget.

The Trump administration believes that the current trade balance is a significant part of the problem. In his first two months in office, President Trump has used tariffs and threats of tariffs to convince trading partners to change their policies. Democrats and even some Republicans think tariffs will raise prices in the U.S. and damage the economy.

Background: Friedman and Samuelson

A few commentators have asked what Milton and Paul would advise if they were still with us. Friedman, a professor at U. of Chicago, is best known for his ideas on the money supply and free trade. He said the quantity of money in circulation was directly related to the inflation rate. He also favored free trade, so he would be against using tariffs as a weapon. Interestingly, Friedman was an economic advisor to Ronald Reagan, so he is generally considered to be a Republican or at least to lean to the right.

Samuelson, a professor at MIT, called himself a cafeteria Keynesian, meaning that he accepted those parts of Keynesian economics that he found most desirable. John Maynard Keynes was a British economist whose ideas became popular during and after WWII—his most well-known theory concerned fiscal policy. According to Keynesian theory, governments should use deficit spending to spur economic growth during recessions or when the economy is operating below full capacity. In contrast, when an economy is operating at full capacity or when inflation is too high, the government should use a combination of tax increases and expenditure reductions to run a surplus budget, dampening economic activity. The deficit spending component of Keynesian economics has been widely employed during recessions and periods of economic growth, resulting in price inflation and increasing debt. Samuelson advocated for the deficit spending part of Keynesian theory.

Samuelson, who favored centralized economic planning and was accused by the right of being a socialist, predicted that the Soviet economy would surpass that of the U.S. He was partly right. A communist country will surpass the U.S., but it’s China, not Russia.

Samuelson served as an advisor to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson.

Both Friedman and Samuelson were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Current Economic Challenges

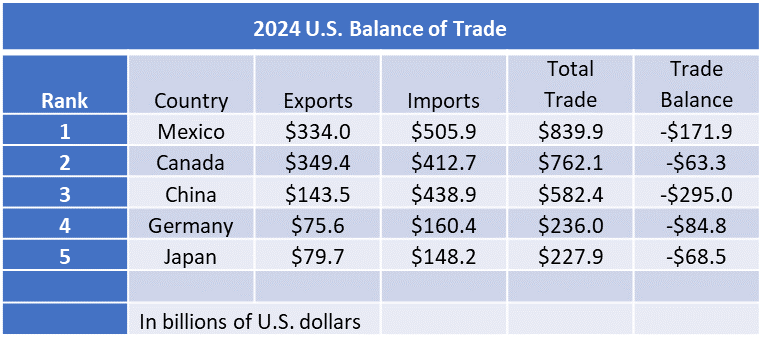

In 2024, the United States had deficits with all its major trading partners. The largest imbalance was with China at $295.4 billion, followed by Mexico at $171.9 billion.

It’s worth noting that the U.S. had trade surpluses with certain countries, including the UK ($11.8 billion) and the Netherlands ($55.5 billion). However, these partners had lower total trade volumes (e.g., the UK at $148 billion and the Netherlands at $123.7 billion).

Like Milton Friedman, some contemporary economists advocate for free and unobstructed international trade. Free trade advocates argue that markets are more efficient when free of government interference and that free markets lead to better resource allocation.

Textbooks on international economics often discuss the idea of comparative advantage. If China and other countries have a comparative advantage because of a much lower labor rate, then producing goods in China leads to lower prices in the U.S. Indeed, U.S. companies have outsourced manufacturing and other activities to China since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2021 leading to much lower consumer prices domestically.

In theory, another benefit of outsourcing labor-intensive tasks is that it leaves U.S. companies free to focus on activities in which they have a comparative advantage. However, one could argue that the U.S.’s comparative advantages over China are quickly shrinking.

The downside of a large trade deficit

There are also important reasons why too much importing of goods from other countries can have negative domestic consequences.

- Loss of jobs – This argument must be qualified. If the U.S. had not already outsourced manufacturing to Mexico and China, outsourcing would lead to the loss of jobs. However, under the current circumstances, bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. would result in higher prices and the need for ongoing tariffs to protect against competition from Mexico and China. So, the U.S. has lost jobs by offshoring, but it is unclear whether many of these jobs could ever be regained.

- Loss of domestic competency—This is an important reason why some activities should be performed within or by the U.S. For example, over the past 30 years, most semiconductor manufacturing has been outsourced to Taiwan. The U.S. has all but lost this critical competency in manufacturing semiconductors and other important products.

Outsourcing key competencies and depending on other countries for key resources gives countries like China bargaining leverage. If a war were to ensue, the U.S. would be disadvantaged. - Currency value – The trade balance impacts a country’s exchange rate. A trade surplus often strengthens the national currency because foreign buyers need it to pay for imports, increasing demand for the currency. A stronger currency can make imports cheaper but might reduce export competitiveness. Conversely, a trade deficit can weaken the currency, making exports more affordable abroad but increasing the cost of imports.

However, the exchange rate is also influenced by the demand for U.S. dollars to use for investments and international trade between other countries. The U.S. dollar has been the reserve currency for international trade for the past fifty years. This may soon change as the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) plan to use a different currency for trade between their group. If successful, this will reduce demand for dollars, weaken the dollar exchange rate, and make imports more expensive. The international currency exchange rate shapes a country’s global trade position. - National debt and financial stability – Persistent trade deficits indicate that a country is spending more abroad than it earns from exports, which may necessitate borrowing from other nations or selling assets to foreigners to finance the gap. Over time, this can increase national debt and make the economy more vulnerable to external shocks, such as shifts in investor confidence. However, deficits aren’t always harmful—countries with substantial foreign investment, such as the U.S., can sustain them without immediate harm. For example, much of China’s currency from its exports to the U.S. is invested in U.S. Treasuries to finance our debt. The balance of trade thus ties into a nation’s long-term financial stability.

The balance of trade influences real-world outcomes, such as job opportunities, the cost of goods, and a country’s economic independence. Whether a surplus that boosts wealth or a deficit that signals potential challenges, it’s vital for understanding and managing an economy’s role in the global marketplace.

The Tariff Effect

When the U.S. imposes a tariff on Chinese goods, the U.S. company that imports the goods from China pays the tariff at the border. The U.S. importer must decide whether to pass the tariff on to consumers by raising their prices or reducing their margins. Generally no company could absorb a 25% tariff without raising prices. The U.S. importer could also try to pressure the Chinese company to reduce their price, but studies show that in the past, this hasn’t worked well. Data from past tariffs, like those during the U.S.-China trade war starting in 2018, backs this up—studies showed U.S. importers bore the brunt of the costs, with some estimates suggesting they absorbed over 90% of the tariff burden rather than it being fully passed back to Chinese firms.

The most likely outcome is that the U.S. importer raises the price to its U.S. customers by the amount of the tariff or perhaps slightly less.

That means the tariff’s effect is to provide revenue to the federal government and raise U.S. prices by a similar amount. In effect, it is a tax on U.S. consumers and businesses.

Trump’s Tariff Strategy

President Trump has imposed tariffs on major trading partners, including China, Mexico, and Canada. He explains that he wants to return offshored jobs to the U.S. and reduce dependence on foreign countries. He also points out that some trading partners are using tariffs to restrict exports from the U.S., so he is simply trying to create a reciprocal policy. Getting specific information about current tariffs imposed by other countries is difficult, so verifying Trump’s claim is not easy.

What would Milton Friedman say about this? In general, Milton favored free international trade and strongly opposed tariffs. Although, he may acknowledge that tariffs could be used as a lever to bring about more balanced, reciprocal trading agreements. The problem he would probably raise is that tariffs reduce competition and, therefore, the drive for innovation. A U.S. company protected from foreign competitors by tariffs is not forced to innovate as it would be by global competitors. Milton would say this is one of the main flaws of tariff strategies.

For the past 20 years, the U.S. consumer has grown accustomed to finding low-priced bargains from China at Amazon, Costco, or Temu. Tariffs on Chinese imports will likely change the prices of consumer goods at these and other outlets.

In addition, retaliatory tariffs would negatively affect exports, so the net effect on the balance of trade is unknowable. It’s a risky game.

How about Paul Samuelson? Samuelson, who generally favored government intervention, was not opposed to using tariffs in some cases. Samuelson recognized that under certain economic conditions, tariffs could have specific effects. For example, he acknowledged that in situations where an economy is operating below full capacity, tariffs might, in the short term, stimulate domestic production and employment.

Samuelson also understood the potential negative consequences of tariffs, such as their impact on consumer prices and the risk of retaliatory tariffs from other countries. Given the circumstances, Samuelson may have been more likely to support at least some of Trump’s tariffs.

Trump claims he is trying to create a level playing field with other countries. China has complex requirements for selling specific products within its borders. For technology products, China may require a U.S. company to form a joint venture with a Chinese company to manufacture or sell products in China. This allows the knowledge and expertise to be transferred to the Chinese partner and, in some cases, even the intellectual property.

China has used intelligent “China first” strategies to leverage its position. In contrast, U.S. companies are primarily concerned with expanding their markets and increasing sales revenue, and they may make decisions that are not in the best interests of the U.S.

Communist, centrally-planned economies do have certain advantages.

Instead of the current tariff war, which may cause prices to increase domestically and eventually prove politically impossible to continue, Trump may be better off renegotiating the NAFTA agreement with Canada and Mexico and imposing reciprocal restrictions on Chinese companies seeking to sell their products in the U.S.

Summary

The U.S. does indeed have a large trade balance deficit with its top five trading partners, totaling about half a trillion dollars in 2024. But the question remains: How can this be remedied without breaking too many eggs?

The U.S. stock market has already declined by over 10%, and the NASDAQ by about 15%. Consumer sentiment is also at a multi-year low, and the country is skeptical of Trump’s strategy.

As many television commentators have observed, Trump’s tariffs will not be politically sustainable. The leaders of China, Mexico, and Canada know this, so they may just wait it out rather than come to the negotiating table.

Milton Friedman would likely oppose Trump’s strategy. Paul Samuelson would likely support it, but we do not have the advantage of asking him.

Trump is correct in stating that the trade deficit is a drag on the economy, but his current strategy may not effectively address the problem. We will have to wait and see and hope that the country emerges from this drama without too much damage.

wonderful! International Organizations Advocate for [Increased Investment in Public Health] 2025 smart

LikeLike